Please note the answers were transcribed from a video interview and have been lightly edited for brevity.

Tell me a little bit about yourself and your journey to fundraising and philanthropy.

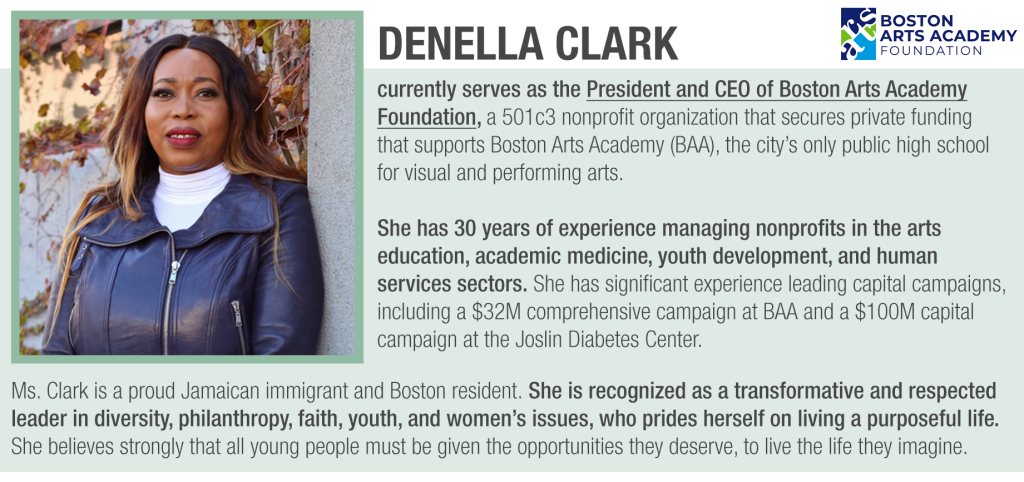

I consider myself a servant leader. Philanthropy and the meaning of philanthropy is the love of humankind or humanity. I have had the pleasure of the last 30-plus years of working for exemplary nonprofit organizations impacting people’s lives and making things better for the public good. I have seen this not only as my own personal mission, but also my ministry in terms of sharing best practices with people as I hope to impart today.

I often say to people I love what I do because I love who I do it for. Right now, it’s young people, who want to be the next generation of artists, scholars, and global citizens. I love the work. I love philanthropy. I love fundraising because it’s just so clear. It’s so tangible that you could see the impact and the difference that you’re making in people’s lives.

I often say to donors that there are many rewards to giving, but for me there is none more rewarding than knowing that you’ve made a difference in the life of a young person. And that’s the work Washington State charter schools are doing through your work with charter schools and helping young people and educating the next generation of leaders.

What is your definition of a capital campaign?

A campaign, to me, could be a capital or comprehensive campaign. It’s an opportunity for the organization to define a case for support where you’re not going to get that funding from public dollars. It may be a situation where one of your charter schools does not want to take out a loan; for example, you start a campaign – capital or comprehensive – by coming up with a case statement and organizing the work around it. This is something that would not otherwise be funded unless through private donations or philanthropy.

Boston Arts Academy embarked on a $32 million comprehensive campaign. How did you and your team approach it? What phases did you engage in? What were some key elements?

The school had never done a campaign before. This was pretty ambitious for them. We are a part of the Boston Public School. When I came, there wasn’t that big of a base of donors. The school is 25 years old. Boston really considers itself a cultural capital, but we are the only public arts high school in the state so we did a few key things to kick off the campaign.

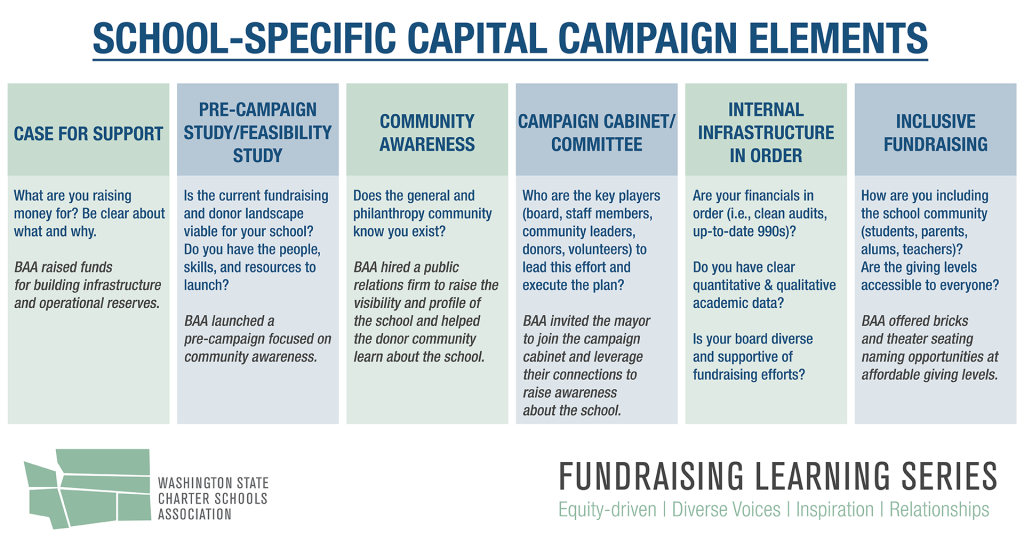

Case for Support

One, we worked with the head of school, who really called for this campaign. It wasn’t the foundation. It was our head of school. They said, “Look, I worry that we’re going to go into this big building, and we’re not going to have the resources we need to really be sustainable.” We worked with her to come up with a case statement, a case for support, and said, “OK, what are some of the big spaces that you’re concerned about?” We had an endowment, but our endowment is currently at seven figures. We’d love to get it to 8 figures to get it over 10 million. What did we need to go out and ask donors for money for? We hadn’t had a true operating reserve. So that’s another thing that we started through the campaign.

Pre-Campaign Study & Community Awareness

We also felt that a lot of people didn’t know about us. We hired a public relations firm to raise our visibility, our profile, make sure that the donor community at large really understood who we were. When some people say they’re going to do a capital campaign, they will do a feasibility study to determine if the donor environment would actually fund the campaign. We didn’t do that. We went right in and said we knew we wanted to do a campaign. I felt confident that we would be successful. What we did was what we called a pre-campaign study, which focused on the case statement and focused on publicity. How are we going to raise our visibility?

Campaign Cabinet

We put together a campaign cabinet, and because we are part of the Boston Public Schools but not fully funded by the public, we asked the then Mayor, Marty Walsh, to be the honorary chair of the campaign. We didn’t have a silent phase, per se. We just put a marker down and said, look, the building’s going to be ready in three years. It ended up taking four years because of COVID. We were going to do a campaign. We started the campaign in 2018, and right out of the gate, we were able to get two $500,000 gifts and a $1,000,000 gift from new donors. Then, we had a kickoff event at the mayor’s residence, which bought a lot of visibility. When you get one big one, it just starts snowballing. The campaign is scheduled to end on June 30, 2025. It was originally a five-year campaign, but because of COVID, we extended it one year; by June 30, we’ll be at $26 million.

Internal Infrastructure

Make sure you have the right ingredients; by the right ingredients, I mean the right mission, leaders, and leadership in terms of people. That your house is in order in terms of your audits and things like that and that you have some inclination or a few key donors that will kick the campaign off and make major investments. If you have a board of directors, you want to make sure you’re at 100% board giving.

Inclusive Fundraising

The last thing I’ll say is working with schools; you also want to make sure that the campaign is very inclusive, that it’s not just all the six, seven, five figure donors. We utilized the building of the campaign to make sure we had opportunities for small dollar donations. For example, when we knocked it down in the old school building, we kept bricks from the original building, and you could gift a brick for $500. The other thing we did is we now have a theater, or some people may call it an auditorium, that has 500 seats. What we did was for our students, families, alumni, anyone. If you wanted to have your name on a seat in a theater, that was $1000. We had people say, hey, if you can’t do the entire $1000 once, you could do a recurring donation.

To me, it’s very important as a school that you bring everybody into the campaign, students, parents, and alumni, and that you want to really be reflective of the entire community.

How did you incorporate equity-driven, organizational value-aligned, and community-centric practices into your capital campaign?

I think it’s important in every organization everyone can give. I really believe in building a culture of philanthropy. I get equally excited about a student, a current student giving $20 as I do an outside donor giving $10,000. I have made it a practice to talk to students, current families, and alumni about the importance of giving back, letting people know that there is a foundation associated with the school.

I think whoever is at the helm within the organization should make sure that they’re saying, “We’re a charter school, but we don’t get all of our money from our state government.” We need to fundraise, and here is why, and not have people feel like because they’re either people of color or because they’re students (that they aren’t being asked to give.) When I joined the organization I’m in now, the board was seated with five white people. There was this feeling that we shouldn’t have asked students, families, and teachers for money. And I said no, everyone can give. Everyone should give. It feels so much better when it’s a collective.

There was a stereotype out there for some reason. That said, for people of color, Blacks, Asians, and Latinos, we don’t give. I said no, that’s actually not true. The number one sector that gets philanthropic dollars is religious organizations. It’s churches. It’s our synagogues. People are giving there. I was very intentional and deliberate about building a board that had people of color. I could show them one of our first donors to the campaign, that put down $500,000, is a Black woman that was married to an NBA All-Star that we lost too young. I think people were shocked like in this community like, a Black woman could give $500,000. I love changing that. Everybody can get involved and honor people’s gifts. We have an alum who every month donates $50. We celebrate all levels of giving and make people feel included.

I think that some people, it’s like the savior mentality that they feel like, we’re going to come in and we’re going to save this little charter school and we’re just going to give the money, but these aren’t people that we would have in our home or our community. There was a stereotype, as I said, that people of color don’t give or that they could only give $100. No, I honor all gifts, and I think it’s important to have a very inclusive campaign where you could say that everyone has contributed.

For the Boston Arts Academy campaign, how was this different or similar to other capital campaigns you have worked on? What are some similarities and differences?

I think the difference between (BAA) and a place like Joslin Diabetes Center here in Boston; it’s a Harvard teaching and research institution. It’s been around for over 100 years, and they not only have grateful patients but tend to draw from demographics with wealth. They are internationally renowned. I remember meeting with a donor from Japan, or we had someone on our board from Venezuela, the wealthiest family we had.

Here at Boston Arts Academy, the makeup of our students and families is something like 85% people of color. They’re grateful too. They just don’t have money. And the big difference here is we’ve had to rely on a lot of private foundations, both family and corporate, corporate foundations, and corporate sponsorships. We’ve had to rely on getting our word out and making the case.

When you’re working for a school that does get public funding, unlike Harvard, some people may say, why can’t the government just give you all of the money? It was much easier to raise money at Joslin Diabetes Center because you didn’t have the competition of being part of a public entity, so it definitely has been more challenging here.

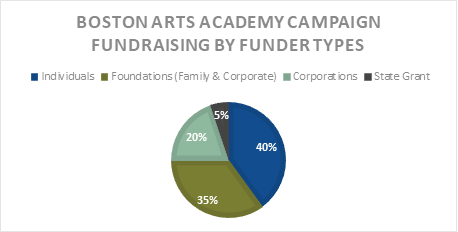

What is the fundraising breakdown between foundations, corporations, and individuals? Which group was easiest to fundraise for, and which group was the most challenging?

About 40% are individuals, 35% foundations that include family and corporate foundations, 5% is a government grant, and the rest are corporations. We get a state grant because we are the only school in the Commonwealth that has a longer (school) day.

I think the easiest would be corporations. Most corporations, especially those giving five- and six-figure gifts, are set up to give money back. They’re the ones that tend to want the naming opportunity or want some benefits associated with their gifts.

I always think it’s harder to get money from individuals. I’m asking you to take money out of your personal pocket and donate. With individuals, once you get their heart, then they’ll give.

With foundations, I find that they’re much more stringent in terms of doing their due diligence, that they’re looking at your audit. They’re asking questions. Is your board diverse? Is your board at 100% giving? So those two categories, I would say, are hard, but in different ways.

I had a foundation that said to me when I came to BAA, “Denella, I know you. I don’t know them.” They had multiple years of deficits in their 990s. That was my second year on the job. We actually had to write a narrative explaining why there were years of deficits and why the board hadn’t responded in a timely fashion. Then we had to make a plan as to how we were going to make sure that there weren’t these deficits going forward. And after all of that, the foundation still said, “We’ll tell you if we’re going to give you the money.” At that point, we had one year of a clean audit where we ended in the black. They still wanted to wait two years to see if we had really done that. Foundations, to me, tend to be very critical, in a good way, of combing through all of the data or vetting and fact-checking you. So foundations tend to be harder than individuals.

Stay tuned for more from Denella on case statements, operational reserve fundraising, tips for engaging individual donors, and more in the coming month!